Considerations

- If a decision has been taken in regard to a request for advice about restituting works of art from the NK collection or other parts of the Dutch National Art Collection, in principle the handling of the application has definitively terminated. The restitution policy does not provide for the option to ‘repeat’ the handling of a case, or to lodge an appeal so to speak. However, in 2010 the Committee did create the option, in consultation with the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, to submit ‘requests for revised advice’. The intent of this procedure is limited. In the case of revised advice, there is no assessment of facts that were already known and are submitted once again to support different arguments, but there is evaluation of new facts that are relevant to the outcome of the advice. In addition, account is taken of the possibility of serious errors of a procedural nature, in particular in regard to the principle of hearing both sides. Summarizing, when handling a request for revised advice, the Committee assesses a case on the basis of two criteria, which are:

(a) new facts that, had they been known at the time the earlier recommendation was formulated, would have led to a different conclusion, and/or

(b) errors during the earlier procedure that resulted in harm to the applicants’ fundamental interests.

- The Committee makes the following comment before it addresses the new facts and procedural errors that have been raised. In their documents the Applicants refer on several occasions to and invoke general consideration c) in the Committee’s recommendation of 12 February 2007 in case RC 1.37 (Mogrobi). This consideration is as follows.

‘The Committee then asked itself how to deal with the circumstance that certain facts can no longer be ascertained, that certain information has been lost or has not been recovered, or that evidence can no longer be otherwise compiled. On this issue, the Committee believes that if the problems that have arisen can be attributed at least in part to the lapse of time, the associated risk should be borne by the government, save in cases where exceptional circumstances apply.’

In recommendation RC 1.49 (Stodel II) of 7 April 2008, however, the Committee reconsidered the applicability of this general consideration in art trade cases. At that time the Committee’s conclusion was as follows.

‘In line with the recommendations with regard to art dealing and the explanation thereof, the Committee has come to the conclusion that consideration c should only apply to the ownership of art by private parties.(…)’

The earlier recommendation dates from after the recommendation concerning case RC 1.49. The Committee will therefore take no further account of the Applicants’ argument that in the earlier recommendation the Committee unjustly did not apply the aforementioned consideration c). The Committee will similarly take no further account of the Applicants’ plea that the aforementioned general consideration c) also applies to new facts.

Procedural errors (criterion b)

- According to the Applicants, the Committee’s draft investigation report in case RC 1.78 of 12 January 2009 unjustly contains no opinion of the Committee about the qualification of the facts summarized in the report and no answer to the question of whether the requirements for restitution have been met. The Applicants contend that as a result of this they were not in a position to respond satisfactorily to the draft investigation report and possibly conduct an investigation themselves. They furthermore argue that this report was unjustly designated as a ‘draft’ because a final investigation report was never submitted to them for comments. The Applicants assert that this also resulted in them not having an opportunity to put forward all their arguments.

The procedure to be followed was explained to the Applicants in a letter of 22 May 2007. The letter contains a statement that the investigation phase would be concluded with a ‘draft report’ to which the Applicants would be able to respond, and after which advice to the Minister would follow. The procedure was also implemented in this way. The Applicants responded to the draft investigation report in a letter of 1 April 2009. The Committee takes the view that the procedure was made sufficiently clear to the Applicants in the letter of 22 May 2007. It is difficult to see why they were not able to put forward all their arguments.

The Applicants’ complaint that the draft investigation report of 12 January 2009 did not contain any opinion of the Committee about the qualification of the facts summarized in the report is in fact a complaint about the Committee’s way of working. This way of working involves publishing the content of the recommendation at the same time as the Minister’s decision about the restitution application. This way of working was also implemented in the earlier recommendation. In this regard there was therefore no error as referred to in criterion (b). Furthermore, contrary to the Applicants’ contention, there is no written or unwritten legal principle with which this way of working conflicts.

In their letter of 25 November 2013 the Applicants also argue that they had no opportunities to dispute the earlier recommendation. According to the Applicants this is contrary to article 13 of the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms. The Committee comments in this regard that the Applicants were and are free to go to the civil court if they cannot reconcile themselves with the Minister’s decision about their restitution application.

- The Applicants argue that in the earlier recommendation the Committee did not give reasons why they took the view that the purchase prices paid to Bachstitz were supposedly in line with the market. The Applicants dispute this view. According to the Applicants there was also no underpinning in the earlier recommendation for why the first sentence of the Ekkart Committee’s sixth recommendation for the art trade was deemed by the Committee to be not applicable.

These complaints concern an, in the Applicants’ view, unsound reasoning in the earlier recommendation. That cannot be considered as an error within the meaning of criterion (b).

- In addition the Applicants argue that it is incomprehensible why Wigman is referred to as a ‘collector’ in consideration 14 of the earlier recommendation and why 1941 is given as the year that NK 1787 was sold to him. According to the Applicants this cannot be deduced from the draft investigation report.

The Committee confirms that in the English translation of the earlier recommendation, consideration 14 erroneously refers to Wigman as a ‘collector’ and gives 1941 as the year that NK 1787 was sold to him by Bachstitz. These additions (‘collector’ and 1941) are not in the Dutch version of the earlier recommendation, which prevails. That cannot be considered as an error within the meaning of criterion (b).

- According to the Applicants the Committee did not conduct sufficient research during its preparation of the earlier recommendation. For example, conducting research in the Bundesarchiv in Koblenz was improperly omitted. In the Applicants’ opinion the 2004 book by Birgit Schwarz, which discusses Hans Posse, was also incorrectly not included in the investigation.

With regard to these complaints the Committee points out that it is up to the Committee to decide how much research is needed to arrive at responsible advice. The Applicants do not specify which information the Committee did not have as a result of the asserted incomplete investigation. In consideration 10 et seq. of this recommendation the Committee will address the Applicants’ references to information about the purchases by Posse and his – alleged – habit of haggling over the selling prices when buying art.

- The foregoing leads to the conclusion that the arguments put forward by the Applicants do not give grounds for the opinion that there are errors within the meaning of criterion (b).

New facts (criterion a)

- The Applicants have underpinned their application with new facts. New facts have also been unearthed by the Committee’s own research, the results of which are recorded in the draft overview of the facts of 8 September 2014. The new facts are discussed below. The discussion is conducted under the following four headings:

– sales to Hans Posse (except NK 2904);

– sale of NK 2904;

– sale of NK 1787;

– sale of NK 2436.

Sales to Hans Posse (except NK 2904);

- The relevant considerations in the earlier recommendation are as follows.

(consideration 16)

‘(…) a) The works NK 620, NK 631, NK 636a-b, NK 864a-b, NK 1552, NK 1553, NK 1627, NK 1798, NK 2484, NK 2581 en NK 2707a-b were sold to Posse for the Führermuseum in Linz in the period from August to 10 December 1940.(…).

The following sums were paid: a sum of NLG 6,000 for NK 620, together with another statue; a sum of NLG 4,750 for NK 631; a sum of NLG 8,000 for NK 636a-b; a sum of NLG 24,000 for NK 864a-b, together with two other gold objects; a sum of NLG 50,000 for NK 1552; a sum of NLG 50,000 for NK 1553; a sum of NLG 30,000 for NK 1627; a sum of NLG 5,400 for NK 1798; a sum of NLG 10,000 for NK 2484; a sum of NLG 12,000 for NK 2581 and a sum of NLG 45,000 for NK 2707a-b.’

(consideration 17)

‘The following applies to the sold objects in categories a and b.

While allowing for the fact that, as a result of the pressures of war, Bachstitz effected transactions with representatives of the Nazis and could therefore count on a certain degree of protection, the Committee is of the opinion that these sales were not involuntary. In cases concerning the art trade, the Committee considers the sole fact that the purchasing party was part of the Nazi regime insufficient to conclude involuntariness, especially if these were transactions for which prices appear to have been paid that were in line with the market and, moreover, no evidence has been found of direct threats or sale under duress. Bachstitz’ statement (see consideration 7) that ‘zoals dat met iedereen het geval was, [hij] af en toe [moest] bukken voor de pressie’ [like everyone, [he] had to bend to pressure every once in a while] refers not so much to a direct threat to Bachstitz himself as to the difficult circumstances during the occupation for art dealers in general.

The Committee also points out that the majority of sales to Posse and Hofer took place in 1940, the first months of the German occupation of the Netherlands (…). Due to his connections in the art world in the early years of the war, Bachstitz was evidently able to operate freely on the market and do business. No evidence was found of coercion towards his person or his family at that stage.’

- The Applicants refer to new facts with regard to the sales by Bachstitz to Posse. In the first place there is information concerning the way in which these sales took place. Part of this information comes from correspondence between Bachstitz and Posse.

The following emerges from the newly available information. The selling prices that Bachstitz requested from Posse for the works NK 636a-b, NK 864a-b and NK 2484 have become known. The purchase prices ultimately paid by Posse for these works were already known when the earlier recommendation was adopted. For example, Bachstitz asked for a sum of NLG 12,000 for NK 636a-b, whereas the purchase price finally paid was NLG 8,000. Bachstitz proposed a sum of NLG 16,000 for NK 2484, whereas the purchase price paid in the end was NLG 10,000. Bachstitz asked NLG 20,000 for NK 864a-b. This work was ultimately sold for NLG 24,000, together with two gold objects (registered under NK 865 and claimed by the Applicants in case RC 1.143), for which Bachstitz requested NLG 3,500 and NLG 4,500. It has now also become known that this transaction took place in May 1941, whereas it had been assumed in the earlier recommendation that the date of the transaction was before 10 December 1940.

At the time of the earlier recommendation it was known that NK 620 was sold together with another statue for NLG 6,000. It emerges from the new information that the asking price for the work NK 620 on its own was NLG 3,750, while the final purchase price was NLG 3,000.

- The prices asked by Bachstitz for a number of other works are not known, but there is other information. For example on 5 September 1940 Posse wrote the following to Bachstitz about NK 1627, which had been offered to him. ‘Ich bin bereit, ihn zu erwerben, wenn Sie mir noch etwas in der Preisforderung entgegenkommen (30.000 fl.).’ Bachstitz accepted this offer.

As regards NK 1552 and NK 1553, which were already known to have been purchased by Posse for NLG 50,000, on 18 November 1940 Posse wrote to Bachstitz that he wanted them ‘wenn sie nicht mehr als 50.000 fl. kosten’. Bachstitz accepted this offer too.

It was already known that the purchase price of NK 2707a-b was NLG 45,000. There is also new information about this sale. On 15 October 1940 Posse wrote to Bachstitz that he wanted to buy the work ‘wenn es nicht mehr als 45.000 Gulden kostet’. Bachstitz replied on 19 October 1940 as follows. ‘Obwohl in diesem Falle keinerlei Nutzen bleibt, nehme ich Ihre Offerte an und erlaube mir wunschgemäss anliegend die Rechnung zu übsersenden.’

A new fact that has become known about the sale of NK 631 is that this transaction took place in September 1941, whereas it had been assumed in the earlier recommendation that the date of the transaction was before 10 December 1940.

- In addition to information about the sales to Posse, the Applicants also refer to a report by Dr Birgit Schwarz of 21 July 2013. The report contains information about Posse and the way he went about his work of acquiring art for the Sonderauftrag Linz. According to the Applicants it emerges from this report that Posse occupied a special position in the Dutch art market because he was buying art on behalf of Hitler. This put him in a position to haggle over the prices that Bachstitz asked.

The Applicants have furthermore compared the sales by Bachstitz to Posse with a number of sales to Posse by other (non-Jewish) art dealers and art sellers, namely D.A. Hoogendijk & Co, P. de Boer, Paardenkooper, N. Beets, Lanz and an unknown vendor. According to the Applicants this comparison shows that Posse was able to obtain greater price reductions from Bachstitz than from the vendors referred to above, who the Applicants assert were not Jewish.

- The Committee finds as follows with regard to these alleged new facts. The information referred to under 10 and 11 about the circumstances of the sales and the information referred to under 12 about Posse and his purchases from other art dealers relate to facts that were not known when the earlier recommendation was adopted. The question, however, is whether these new facts, had they been known, would have resulted in the conclusion that there were indications that it was highly likely that there was selling under duress.

It emerges from the information about the circumstances of the sales that in the case of four of the works now being claimed, as well as with regard to NK 865, which is the subject of case RC 1.143, there was a difference between Bachstitz’s asking price and the purchase price ultimately paid by Posse. The biggest difference between asking price and purchase price was in the sale of NK 2484, where Posse succeeded in obtaining a reduction of 37.5% in the asking price. The smallest difference concerned the sales of NK 864a-b and NK 865, where Posse was able to negotiate a reduction in the asking price of 14.28%. It moreover emerges from the new information that Bachstitz agreed to Posse’s offers for three NK works and that Bachstitz, as he said himself, made no profit on the sale of NK 2707.

In the Committee’s opinion, however, this new information does not contain any indications that the sales concerned took place under duress. In this connection the Committee points out that a difference between the asking price and the purchase price is normal in the art trade. The differences observed in this case, in one instance as much as 37.5% of the asking price, are not of such a magnitude that they alone give reason for being able to consider these sales as not having been voluntary. Similarly the fact that Bachstitz made no profit on the sale of NK 2707 is not sufficient for assuming that the sale was therefore involuntary.

Even when seen in the light of the new information about the sales to Posse by other art dealers and the information about Posse’s working methods, the new information does not lead to a conclusion that is different from that in the earlier recommendation. As regards the sales to Posse by other art dealers, it emerges from the information supplied by the Applicants that, among other things, there were often no negotiations about the asking price associated with these sales, or there were modest price reductions, with a maximum of ten percent in one case. In so far as it could be concluded from this that Posse was able to get relatively greater reductions on the asking prices proposed by Bachstitz, this does mean that the sales by Bachstitz took place under duress. The new information gives insufficient indication for this.

As far as the information about Posse’s working methods are concerned, as referred to in the Schwarz report, the Committee takes the view that what is described in that report is too far removed from the sales that are now at stake.

- In their letter of 10 June 2014 the Applicants also referred to the registration of a bronze cupid on www.lostart.de since March 2014 as a new fact. According to the Applicants the circumstances relating to the sale of this statue by Bachstitz in October 1941 are identical to the circumstances concerning the sales to Posse that are now under discussion. In the Applicants’ opinion the aforementioned registration is an indication that the bronze cupid was sold involuntarily, which in their opinion is also significant in regard to the sales currently at issue.

However, this registration cannot be designated as a new fact within the meaning of criterion (a). No implications with regard to the sale of other artworks by the same vendor can be associated with solely the registration of a particular work of art on www.lostart.de.

- The mere circumstance that the sale of NK 864a-b took place in May 1941 and that of NK 631 in September 1941, whereas in the earlier recommendation it had been assumed that the sales took place before December 1940, does not lead to the conclusion that they were involuntary sales. In this regard the Committee also refers to consideration 10 of the recommendation concerning case RC 1.143.

- It follows from the foregoing that what the Applicants have argued and what has emerged from the Committee’s own investigation does not give reason to revise the recommendation with regard to case RC 1.78 in so far as it relates to the Applicants’ claim on NK 620, NK 631, NK 636a-b, NK 864a-b, NK 1552, NK 1553, NK 1627, NK 2484, NK 2581 and NK 2707a-b.

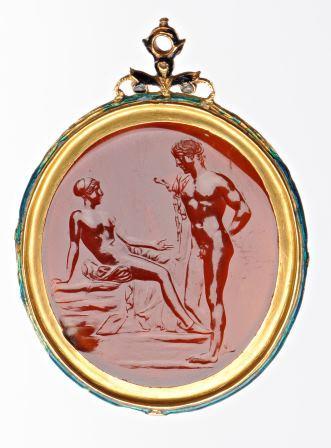

NK 2904

- New information has become known about the sale of NK 2904 (a carnelian cameo) to Posse on 21 June 1941. Among other things a letter from Bachstitz to Posse of 26 May 1941 is important. In it he writes as follows.

‘Für Ihre freundliche Auftrage danke ich Ihnen bestens. Das sogenannte Stirnband – warscheinlich Spiralarmband – gehört, ebenso wie die Karneol-Gemme, meiner Privatsammlung an. Die Gemme erwarb ich 192o für Hfl. 6ooo.-, das Stirnband 1930 für Hfl. 18.ooo.- / Da die Stücke Teile meiner Privatsammlung sind, wiederstrebt es mir in Anbetracht Ihres sich gesetzten Ziele Ihren event. Erwarb als Geschäft anzusehen. Gerne überlasse ich Ihnen das eine oder andere Stück für meinen Einkaufspreis.’

It emerges from a letter of 21 June 1941 from Posse to the head of the Reichskanzlei in Berlin, Dr Lammers, that Posse did indeed acquire NK 2904 (referred to as ‘Karneol-Gemme’) for NLG 6,000.

According to the Applicants it follows from the letter of 26 May 1941 that NK 2904 belonged to Bachstitz’s private collection, so their claim to this work should be assessed in accordance with the standards for privately owned art.

- Bachstitz’s statement in the aforementioned letter of 26 May 1941 that NK 2904 belonged to his private collection was not known when the earlier recommendation was adopted and in this regard is a new fact. In order to answer the question of whether this fact would have resulted in a different conclusion had it been known when the earlier recommendation was adopted, the Ekkart Committee’s third recommendation for the art trade is of prime importance. This recommendation is as follows.

‘If there are sufficient indications that a work of art did not belong to an art dealer’s trading stock but to his private collection, applications for restitution will be addressed in accordance with the standards for privately owned art.’

It is stated in the notes to this recommendation that ‘clear indications that is was private property instead of hard evidence are deemed to be sufficient’.

The Committee is of the opinion that Bachstitz’s statement in the letter of 26 May 1941 is a clear indication that NK 2904 did not belong to the gallery’s trading stock but to Bachstitz’s private collection. The consequence of this is that the restitution application, in so far as it relates to NK 2904, must be dealt with in accordance with the standards for privately owned art.

- In the case of privately owned art, the reversal of the burden of proof, as expressed in the third recommendation of the Ekkart Committee (2001), applies.

‘The committee recommends that the sale of works of art by private Jewish individuals in the Netherlands on or after 10 May 1940 should be considered as forced sales unless there is express evidence to the contrary (…)’

In the absence of express evidence to the contrary, the sale of NK 2904 to Posse must be designated as involuntary.

- The Committee then raises the question of whether a payment obligation should be specified in regard to restitution of NK 2904 in connection with the consideration received when the work of art was sold. Under the present restitution policy, repayment is only addressed if and in so far as the former vendor or his heirs actually had free control of the proceeds of the sale, with the former vendor or his heirs being given the benefit of the doubt if this cannot be ascertained.

The correspondence between Bachstitz and Posse shows that Bachstitz received NLG 6,000 for the artwork. It also emerges from the same correspondence that Bachstitz sold it so he could pay for his sick son to stay in a sanatorium in Switzerland. This was why he asked Posse to pay in Swiss Francs. Although Posse passed this request on to Dr Lammers, head of the Reichskanzlei, in the end payment was made in guilders.

It is known that Bachstitz’s son was seriously ill with tuberculosis, and for that reason was probably admitted to a sanatorium in the Engadin, Switzerland, in June 1941. He died in 1943. In the committee’s opinion Bachstitz’s choice to have his son stay in Switzerland, a country that was not occupied by the Nazis, cannot be seen in isolation from the threat to his son in areas occupied by the Nazis. The committee considers it plausible that Bachstitz used the proceeds of selling NK 2904 to pay for his son to stay in Switzerland. In these circumstances the Committee’s opinion is that there can be no question of repayment of the proceeds of the sale.

- The foregoing leads to the conclusion that the Committee will advise the Minister to restitute NK 2904 to the heirs of Kurt Walter Bachstitz.

NK 1787

- The Committee’s conclusion with regard to NK 1787 in consideration 14 in the earlier recommendation was as follows.

‘The Committee finds that the Bachstitz Gallery either sold or consigned three works to Dutch buyers – who were, as far as is known, not collaborators. In the absence of proof to the contrary, the Committee deems it plausible that these were everyday transactions and that there was no question of duress.

(…)

– With respect to NK 1787, the Committee considers it plausible that the Bachstitz Gallery sold the work to a Dutchman (Wigman), who sold it to Posse in 1944.’

- In the first place the Applicants referred to a statement by W.A. Hofer of 5 June 1945.

‘Kurt Walter Bachstitz, dem man in Den Haag sein Geschäft (Kunsthandlung, international) beschlagnahmt hatte, 1943, besorgte ich trotz gröβter Schwierigkeiten mit Erlaubnis von Göring Ausreise aus Deutschland (Juni 1944, & Einreise in die Schweiz. (…)’

According to the Applicants this statement proves that Bachstitz’s gallery was confiscated in 1943. The Applicants take the view that sales after this confiscation cannot be considered as voluntary.

The Committee did not know of this statement when the earlier recommendation was adopted. In this regard this statement is therefore a new fact within the meaning of criterion (a). However, the Committee notes that this statement is not supported by any other document or statement made by a witness. In the Committee’s investigation, for example, no indications were found in the Chamber of Commerce’s register of companies file on the Bachstitz Gallery that the company was registered in the context of Regulation 189/40 as a partially or wholly Jewish enterprise, or that a Verwalter (administrator) or Treuhänder (trustee) was appointed by the Germans to take charge of it. Similarly no indications were found in the archive of the Abteilung Feindvermögen (Enemy Assets Department) of the Reichskommissariat in den besetzten Niederländischen Gebieten (Reichs Commissariat for the Occupied Dutch Territories), which is in the National Archive, that the Bachstitz Gallery was put under German control during the occupation.

In view of this the Committee finds that the sole statement of Hofer, as referred to above, is insufficient to make it plausible that the gallery was confiscated in 1943.

- The Committee’s investigation into the sale of NK 1787 has unearthed a number of new facts. For example, correspondence was found between Dr E. Göpel and Dr R. Oertel, both working for the Sonderauftrag Linz, about the purchase of the work. Among other things, it emerges from these letters that the asking price for the work was NLG 75,000. Other documents that were found include a bill for the work from J.G. Wigman to the Sonderauftrag Linz for NLG 70,000 and a letter of 5 May 1944 in which Wigman confirms receipt of this sum. A list of acquisitions in the Netherlands by the Sonderauftrag Linz during the last years of the occupation includes the following.

‘[Übertrag]

70.000.– 8.5 J.G. Wigman-Haag 1 florentin. Rahmen 15.Jhdt’

New information about Wigman has also become known, as described in the draft overview of the facts. Originally he was a furniture maker, but in May 1940 he became a branch manager with the art dealership Firma D. Katz in The Hague. He lived in the art dealership’s branch at Lange Voorhout 35 in The Hague. It can be deduced from a letter from Göpel of 20 October 1942 that after the departure of Nathan and Benjamin Katz the premises were at the disposal of Posse for packaging and storing paintings for the Sonderauftrag Linz. Copies of various bills confirm this interpretation. Several bills in Wigman’s name for paintings and silver items that were supposedly delivered to the Sonderauftrag Linz in 1944 were also found. All these bills and receipts were signed by Wigman and no other names were referred to on the documents.

- The Committee has asked itself the question of whether the aforementioned new facts, had they been known at the time the earlier recommendation was adopted, would have led to a different conclusion. The Committee answers this question in the negative. When the earlier recommendation was adopted, the Committee had deemed it plausible that the Bachstitz Gallery sold NK 1787 to Wigman, who sold it on to Posse in 1944. Clearly this last step cannot be correct because Posse died in 1942. What was meant, as has now also emerged from the new information, is that the work was sold to the Sonderauftrag Linz. In the Committee’s opinion, also on the grounds of the new facts it is not plausible, as contended by the Applicants, that Bachstitz sold the work directly to the Sonderauftrag Linz. The bill for the work with the name of Wigman on it and the letter of 5 May 1944, in which Wigman confirms receipt of the purchase price, indicate a sale of the work by Wigman to the Sonderauftrag Linz. The Committee therefore confirms its conclusion in the earlier recommendation.

NK 2436

- The Committee’s conclusion with regard to NK 2436 in consideration 15 in the earlier recommendation was as follows.

‘During the occupation, the Bachstitz Gallery sold four works to German museums. In the light of the purchase prices paid for them, it is again reasonable to assume that these were also normal transactions with clients. Nor is there any evidence that Bachstitz was pressurised. In connection with this, the Committee refers to Bachstitz’ statement quoted in consideration 7, namely that he sold work to “musea-directeuren, met wie hij lang vóór de oorlog zaken had gedaan” […museum directors, with whom he had done business long before the war.].

(…) During the occupation, NK 2436 was sold for an unknown sum to K. Martin, director of the Kunsthalle in Mühlhausen.’

- In so far as the Applicants referred to the statement by Hofer of 5 June 1945 as a new fact, it is sufficient for the Committee to refer to its conclusion about this statement in consideration 23 of this recommendation.

- The Applicants submitted, as a new fact, a bill of 18 February 1943 on the Bachstitz Gallery’s letterhead from the Generallandesarchiv (State Archive) in Karlsruhe. It can be deduced from this bill that Bachstitz sold NK 2436 to Dr Kurt Martin on 18 February 1943 for NLG 45,000. Correspondence between Bachstitz and Martin about the sale of NK 2436 was also found. Furthermore a letter from Bachstitz to Posse was found in which it can be deduced that at the end of 1940 Bachstitz offered the painting to Posse for NLG 35,000.

The Applicants moreover referred to the book by Tessa Friederike Rosenbrock, Kurt Martin und das Musée des Beaux-Arts de Strasbourg. Museums- und Ausstellungspolitiek im ‘Dritten Reich’ und in der unmittelbaren Nachkriegszeit. The book appeared in 2012 and it contains a great deal of information about Martin. The Committee’s investigation also found information about Martin from index cards compiled by the Americans after the war.

- The facts referred to in consideration 28 above were not known when the earlier recommendation was adopted. The Committee answers as follows the question of whether these facts, had they been known at that time, would have resulted in a different conclusion about the sale of NK 2436.

The selling price of NK 2436 that has now become known (NLG 45,000) does not in itself indicate that this sale was involuntary. The circumstance that Bachstitz very probably offered Posse the work at the end of 1940 for a sum of NLG 35,000 does not change this. Contrary to the Applicants’ assertion, it cannot be concluded on the grounds of the asking price in 1940 that the sale in 1943 for a sum of NLG 45,000 was involuntary.

On the basis of the new information about Martin, the Applicants have contended that he was supposedly ‘someone like Göpel’. In the Committee’s opinion, however, this information does not provide sufficient basis for this contention, leaving aside the conclusions that should arise from it. The Committee notes in this connection that the correspondence about the sale of NK 2436 between Bachstitz and Martin that has now become known contains no indications that this sale took place under duress.

- As regards the date of the sale of NK 2436 that has now become known, 18 February 1943, the Applicants have referred to the similarity to the sale of NK 1892. The Committee also notes that the date of this sale is close to that of NK 1892 on 10 June 1943. As pointed out in consideration 18 of the earlier recommendation, circumstances became more and more perilous for Bachstitz in the run-up to his arrest in July 1943. According to this same consideration, however, at that time the Committee did not deem just the generally threatening situation for Bachstitz to be important. It also attached importance to the fact that the sale of NK 1892 took place after the declaration of Bachstitz as a Volljude (full Jew) one month before and that the buyer was Göpel, who in 1943 had arranged for Bachstitz to be exempt from wearing a Star of David. In the Committee’s opinion these differences mean that the sale of NK 1892 cannot be compared with that of NK 2436 in view of the Ekkart Committee’s recommendations for the art trade. These recommendations are after all based on the assumption ‘that the art trade’s objective is to sell trading stock, so a significant fraction of transactions, even by Jewish art dealers, in principle constituted ordinary sales’. There is only reason to depart from this assumption if there are indications that it is highly likely that there was selling under duress. The generally threatening situation for Bachstitz personally and also the circumstance that the sale of NK 2436 took place in February 1943 are not sufficient for this.

- In so far as the Applicants referred to the registration on www.lostart.de of a number of other artworks that were sold by Bachstitz to Martin, the Committee concludes that this registration cannot be designated as a new fact within the meaning of criterion (a). No implications with regard to the sale of other artworks by the same vendor can be associated with solely the registration of a particular work of art on www.lostart.de, even if they were sold to the same buyer.

- The foregoing leads to the conclusion that the Committee will advise the Minister to let the rejection of the claim to NK 2436 stand.